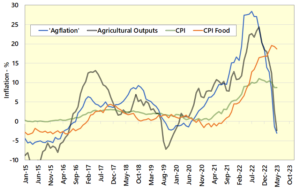

After rising sharply since 2021 and peaking in July 2022 at 28.4%, agricultural inputs’ inflation (Agflation) has been in free-fall during the first half of 2022 and has become deflationary. The latest estimates suggest that agricultural input prices in May 2023 are 3% lower than in May 2022. Agricultural output prices have broadly mirrored the trend for agricultural inputs and have also become deflationary, currently standing at -2.3%. This is in sharp contrast to food prices (depicted by CPI Food), which in May 2023 are estimated to have risen by 18.7% year-on-year.

Although, it appears that food prices for consumers are continuing to rise whilst agricultural prices are falling, importantly, there is a lag between how agricultural prices evolve and how these prices are reflected in retail prices. Back in 2017, when agricultural output prices reached their highest point in May of that year (at 13.2%), the CPI Food index did not peak until the following November (at 4.1%). This reveals a lag of about 6 months and indicates that the highest extent of inflation in food prices was significantly lower than for agricultural outputs. A key reason for this is that agricultural raw materials are one of several inputs that go into supplying food to consumers. Other inputs such as labour, energy, and packaging are also significant, and traditionally are much less volatile than agricultural prices.

Andersons’ Agflation index builds upon on Defra price indices for agricultural inputs and weights each input cost (e.g., animal feed) by the overall spend by UK farmers. Andersons then provides a more up-to-date estimate of the price index for each input cost category. The Agricultural Outputs index is compiled in a similar manner. Defra price indices for agricultural outputs are weighted based on their overall contribution to UK farming output. Andersons then provides more recent estimates for each output category, with the index being updated as the official Defra data becomes available.

Brexit Covid and war

That said, the combined effects of Brexit, Covid and the Russia-Ukraine conflict have exerted multiple pressures on both agricultural commodities, labour and energy inputs meaning that recent CPI Food inflation has almost reached 20%. However, there are signs that food price inflation might have peaked in March 2023, about 7 months after agricultural output prices had done similar.

Furthermore, although the chart above shows that inflation is trending downwards, it disguises that agricultural and food prices today are substantially higher than they were two years ago, as the indexed chart below shows. Agricultural input prices are 24% higher, agricultural outputs are up 15% whilst food prices are up by 29% in that time. In this time, prices elsewhere in the economy, denoted by the CPI index are also up by 18%. This reveals the corrosive pressure that inflation exerts on consumers’ incomes. Understandably, workers will seek pay rises to mitigate these increases. This, in turn, will mean that inflationary pressure across the economy generally will continue to linger, especially as annual inflation (8.7% (CPI)) remains way higher than the Bank of England’s 2% target.

further challenges ahead

With consumer incomes under pressure, there is even greater focus on food prices and, by implication, the prices that farmers receive. All the while, farmers too are contending with their costs being significantly higher than two years’ ago. This signifies further challenges ahead, at a time when recent Free Trade Agreements with Australia and New Zealand have entered into force. Although farmers in those countries have also had to contend with inflationary pressures, it suggests that a delicate balancing act will be needed so that British prices remain competitive, whilst permitting farmers to cover the significant cost increases that they have experienced in the past two years.

Indeed, a key reason why agricultural inflation has come down is because the annualised figures compare with a given month a year earlier, a period when the world was adjusting to the shocks caused by the start of the Russia-Ukraine conflict. When annual inflation is compared to a period after which costs had increased considerably, it is unsurprising that the rate of increase has slowed, or turned negative in the case of agflation.

Indeed, a key reason why agricultural inflation has come down is because the annualised figures compare with a given month a year earlier, a period when the world was adjusting to the shocks caused by the start of the Russia-Ukraine conflict. When annual inflation is compared to a period after which costs had increased considerably, it is unsurprising that the rate of increase has slowed, or turned negative in the case of agflation.

In such times, it is more important than ever for farmers and those that transact with farmers to be aware of the costs that farmers face. The Agricultural Budgeting and Costing Book contains all the farm and rural business information you need in one publication. It is concise, clear, and easy-to-use. The information is updated every six months, so you are always using the most relevant data, something which is especially vital during inflationary periods. The contents include;

- Fully updated gross margins for all farming sectors, crops, and livestock, including net margins for key enterprises.

- Sensitivity analysis and discussion of market prospects.

- The widest range of information on alternative enterprises, diversification, and non-farming income sources available in any UK publication.

- Explanation of the support systems and grants across GB, including BPS rules and rural grants. An outline of post-Brexit farm policy.

- Farming costs including forage, feed, fertiliser, and pesticides.

- Overhead cost data covering machinery, labour, contracting, building costs, and rents.

- A vast array of general reference information for the farming sector.